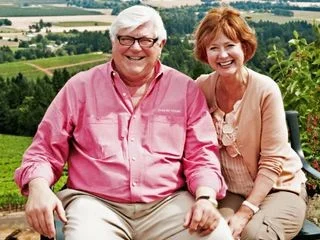

Ken and Grace Evenstad have always loved the chardonnay and pinot noir from Burgundy. In the late 1980s they launched one of the most successful pinot noir houses in the Willamette Valley and sought to pursue their dream of making exceptional wine in the United States. Indeed, Domaine Serene has been winning awards ever since.

But the Evenstads couldn't let go of their Burgundian dreams. In 2015, they purchased a 15th century chateau -- Chateau de la Crée -- in Santenay. I would think that breakthrough would cause a stir in the chateau's tiny village of Santenay. After all, it wasn't that long ago that Robert Mondavi was rudely rebuffed by the French in an attempt to plant a vineyard in Languedoc.

But, the Evenstads were no Mondavis.

"The deal was completed in a few months," said Ryan Harris, president of Domaine Serene.

An American wine producer buying an historic chateau of this order is more unusual than a French producer buying wine property in the United States. Moet-Chandon was among the first to do launch a sparkling wine company in California in 1973. Champagne makers Taittinger and Roederer soon followed. Then came Clos du Val, Dominus, Opus One (a partnership of Mondavi and Baroness Philippine de Rothschild). In Oregon, Burgundian Robert Drouhin of Maison Joseph Drouhin raised eyebrows -- and prestige -- when he launched Domaine Drouhin in Oregon's Willamette Valley. But the Evanstads were the first Oregonians to own a chateau in Burgundy.

Grace Evenstad, who was recently hosting a wine dinner in Naples, Fl., said the differences between making wine in Oregon and France were clear one day when she showed a Burgundian winemaker their Willamette Valley vineyards.

"She said to me, 'Which rows are yours?'" Evenstad said.

In Burgundy, it is common for a vineyard to have multiple owners.

Harris said that throwing a lot of parties, meeting neighbors, and developing good relations with local officials paved the way for the purchase. But, the transition to making good wine was not so smooth.

Evenstad said, "Everyone is now gone."

Whether they left on their own or were replaced wasn't clear, but she said that they were surprised by the lack of "science" at Chateau de la Crée. She said vineyards lack adequate spacing between rows and even if the vineyards were bio-dynamically farmed -- whatever that means in France -- the pesticides and other chemicals from neighboring vineyards were wafting onto those of Chateau de la Crée.